Indirect vs. Direct Characterization | Definitions, Examples, & Differences

- Melchior Antoine

- Oct 30, 2025

- 7 min read

Characterization is key to proper storytelling. Whether your story works or fails depends on how well you execute characterization. And it is often felt that indirect characterization is preferable to direct characterization. This is also the same principle behind the old storytelling adage: “Show, don’t tell.”

With indirect characterization, the author allows the character to reveal themselves and personality through their words and actions or even through other character perspectives. In the case of direct characterization, the author tells the reader directly about the character.

Because of this, plays tend to rely more heavily on indirect characterization than direct characterization. In a play, there are hardly any of what are called authorial intrusions. This is where the author inserts themselves directly into the story, as is the case with a novel.

Instead, the story or plot of the play is carried out almost entirely by the actions and dialog of the actors in the play. Nonetheless, even in plays, character perspectives and intelligent dialogue can be used to pull off indirect characterization. In this article, we discuss how writers use direct and indirect characterization, using examples from Macbeth, Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, and The Great Gatsby.

What is direct characterization?

Direct characterization refers to an author describing a character in a direct and an unsubtle way to the reader. It is seen often as the inferior form of characterization compared to the alternative of indirect characterization. In an ideal narrative, characterization should be revealed through various literary devices, such as:

Intelligent dialogue

Character behavior

A good example of direct characterization is from The Great Gatsby (published in 1925) when the author introduces the character of Tom Buchanan:

Two shining arrogant eyes had established dominance over his face and gave him the appearance of always leaning aggressively forward. Not even the effeminate swank of his riding clothes could hide the enormous power of that body—he seemed to fill those glistening boots until he strained the top lacing, and you could see a great pack of muscle shifting when his shoulder moved under his thin coat. It was a body capable of enormous leverage—a cruel body

Tom Buchanan is here being described negatively as arrogant and capable of enormous cruelty. He is clearly meant to be seen as a villainous antagonist to the protagonist, Gatsby. This is seen through the course of the play, where it is revealed that he is violent with his mistress, Myrtle, and even breaks her nose in a bout of domestic violence.

An even more extreme example of direct characterization is the mean and miserly Ebenezer Scrooge from Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (published in 1843). Here he is being described on the first page of the novel before encountering the ghost of his former business partner Marley:

Oh ! But he was a tight-fisted hand at the grindstone, was Scrooge! a squeezing, wrenching grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner! External heat and cold had little influence on him. No warmth could warm, no cold could chill him. No wind that blew was bitterer than he, no falling snow was more intent upon its purpose, no pelting rain less open to entreaty. Foul weather didn't know where to have him. The heaviest rain and snow and hail and sleet could boast of the advantage over him in only one respect, -- they often "came down" handsomely, and Scrooge never did.

The description is meant as satirical and humorous, which is further enhanced by the inversion or anastrophe in the first line of the excerpt, and the asyndeton (a lack of conjunctions) used throughout the passage. It’s obvious that Scrooge is a stereotype of the mean and miserly old man. It’s true that such direct characterization is often seen as inferior.

However, here it works quite well because of the humorous intention and because of the point of the story, which is the reformation and redemption of the miserly Scrooge to match the warm and giving spirit of Christmas.

Get in touch for help in editing your work |

What is indirect characterization?

Indirect characterization relies on the reader to figure out the kind of person their character is without being told. Before we proceed, let’s provide a formal definition of the term:

Indirect characterization is a form of character depiction that relies on the actions, dialogue, and other character perspectives instead of direct statements by the author.

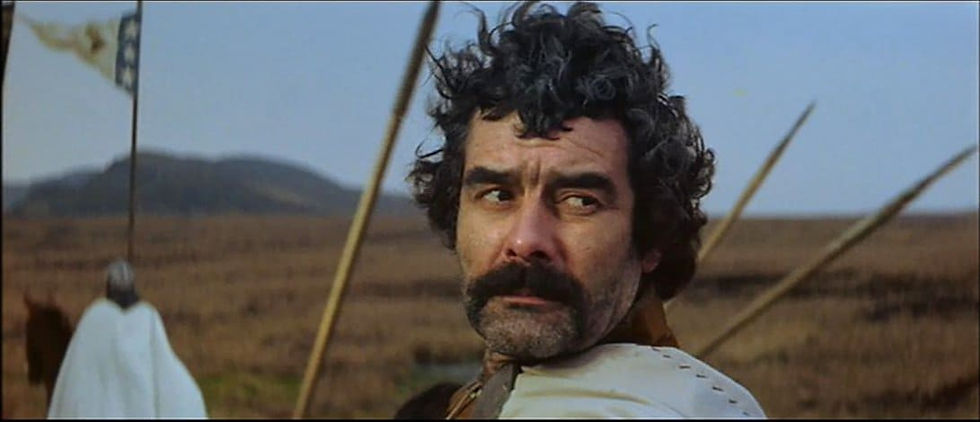

A good example of indirect characterization is Lady Macbeth in the play Macbeth. At first, it seems obvious that Lady Macbeth is a vile and evil character. The only thing we admire about her is her love of her husband. Together, the two of them constitute a kind of Medieval Bonnie and Clyde wreaking havoc upon the world.

She seems dedicated to the cause of making her husband the king of Scotland, even if it means making a bargain with the devil. This involves killing the current ruler of Scotland, King Duncan, as he sleeps as a guest in the Macbeth household.

After initially agreeing to the conspiracy, Macbeth changes his mind about killing “Good Duncan” in the famous Dinner Scene. However, Lady Macbeth quickly makes him “turn back” in the same scene, and she uses what can only be described as gruesome and demonic imagery to do so.

She describes the agreement or decision to become king as a commitment that she would be willing to sacrifice even the most innocent being for:

I have given suck, and know

How tender ’tis to love the babe that milks me.

I would, while it was smiling in my face,

Have plucked my nipple from his boneless gums

And dashed the brains out, had I so sworn as you

Have done to this. (Act 1, Scene 7)

This extreme language can even be seen as a direct characterization of Lady Macbeth. She is portrayed as an ambitious woman who is willing to violate every humane and moral code to gain power on behalf of her husband. However, Lady Macbeth’s enthusiasm to kill may well be performative.

We get a hint of that when she admits that she herself can’t kill Duncan for a specific reason:

Had he not resembled

My father as he slept, I had done ’t. (Act 2, Scene 2)

What is the subtext here? The lady who boasted about her willingness to kill her own newborn babe cannot bring herself to kill a man because that man resembles her father. This is a form of indirect characterization that can help explain Lady Macbeth’s tragic fate. She eventually grows insane from guilt and remorse and ends up committing suicide before the play ends.

These two lines of dialogue foreshadow Lady Macbeth’s sad fate. It also suggests Lady Macbeth’s motives for killing Duncan. Lady Macbeth may have been obsessed before and above everything else with being her husband’s handmaiden in the project of securing the Scottish kingship. She suppresses her own human or feminine nature in favor of ambition with devastating consequences.

Another example of indirect characterization is from The Twelfth Night with the character of Orsino. Orsino is portrayed as a kind of trope. He is the courtier in love with the idea of love. It is the kind of love typically portrayed in a Petrarchan Sonnet, where the man is in love with a woman who is engaged to someone else, not interested in him, or, better yet, dead.

Throughout most of the play, he is obsessed with pursuing Lady Olivia, who shows no interest in him. He is told by Viola (who is a woman pretending to be a man who is in love with Orsino) that he should relent and simply accept that Lady Olivia is not interested in him. Viola asks him to think of what he would do if a lady for whom he has no affection loved him as he loves Olivia. The idea offends him, and he responds:

There is no woman’s sides

Can bide the beating of so strong a passion

As love doth give my heart; no woman’s heart

So big, to hold so much; they lack retention.

Alas, their love may be called appetite,

No motion of the liver but the palate,

That suffer surfeit, cloyment, and revolt;

But mine is all as hungry as the sea,

And can digest as much. Make no compare

Between that love a woman can bear me

And that I owe Olivia. (Act 2, Scene 4)

Orsino apparently believes that there is no woman on earth who could love as well as he loves. He is a type of character who is obsessed with the passion of emotions, and the unrequited love of the woman he pursues is the perfect opportunity to experience and act out such emotions.

We can also see the indirect characterization of Orsino based on the reaction of other characters. In particular, the clown of the play, Feste. In one scene, the clown mocks his constantly changing emotions:

Now the melancholy god protect thee and the

tailor make thy doublet of changeable taffeta, for thy

mind is a very opal. I would have men of such

constancy put to sea, that their business might be

everything and their intent everywhere, for that’s it

that always makes a good voyage of nothing.

Farewell.

The clown "praises” Orsino for his shallow and changing emotions. The phrase "thy doublet of changeable taffeta" refers to a jacket made of a type of cloth called taffeta. In short, Feste hopes that Orsino's clothes match his lack of emotional consistency. The same idea is suggested with reference to opal, a kind of precious stone that refracts light into rainbow colors.

Having Orsino’s business described as “everything and their intent everywhere” and making a good voyage of nothing also enforces the pointlessness of his childish lack of emotional constancy. This characterization of Orsino is justified when we see him quickly forget about his love for Olivia after finding out that his young male page is a beautiful woman who is in love with him.

Cite this EminentEdit article |

Antoine, M. (2025, October 30). Indirect vs. Direct Characterization | Definitions, Examples, & Differences. EminentEdit. https://www.eminentediting.com/post/indirect-vs-direct-characterization |